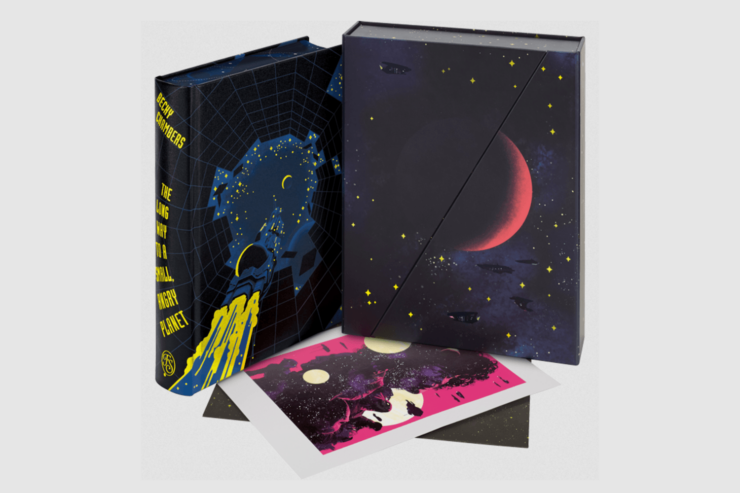

Explore the far future with the first illustrated edition of The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet—now available from The Folio Society in a truly galactic limited edition. We’re thrilled to share several of the exclusive interior illustrations by artist Zoë van Dijk alongside commentary from Becky Chambers, plus the author’s introduction to the new edition.

The Fishbowl

On one of the shelves in my office, I have a small clay figurine of Dr Chef that my wife made for me almost a decade ago. Zoë had no knowledge of this, and yet, the resemblance between her rendition and said figurine is downright uncanny. That’s him. That’s my otter-caterpillar-gecko friend.

Ashby & Pei

Nowhere in the text do I say that Ashby is jacked. I am so glad Zoë understood, intuitively, that Ashby is jacked. I mean, come on. Pei’s a woman of good taste.

Also, I love this depiction of an Aeluon body. I sometimes see fanart of Pei that is more traditionally feminine by human standards, and while that’s all good, I can really tell that Zoë paid a lot of attention to how I described Aeluons and Pei in particular.

Kizzy and the mines

Once again, I’m floored by how well Zoë managed to capture the shot in my head. That slow crane upwards, the dawning realization of ‘oh no.’ I had trouble writing this chapter, for reasons I can’t remember now, and this gives me such an incredible feeling of oh wow, managed to get it out, apparently.

Toremi Attack

It’s a requirement of my profession that I am a sucker for brightly colored spaceship art. This is some damn fine brightly colored spaceship art.

Introduction

A year is not a measure of time, but of movement. It messed me up when that was pointed out to me, and I hope, grinning as I write this, that I’ve now paid the feeling forward. Time, you see, is an inescapable component of our universe, woven into the fabric of space in ways I don’t fully grasp, marching ever forwards and never looking back. A year, on the other hand, measures a single lap of our planet around the sun. A year itself is broken down into days (which mark the rota.tion of said planet around its axis), weeks (which mean nothing) and months (which roughly match the orbital period of our moon). We’re not measuring time, because we can’t, not really. Time is ineffable, on its own. It can speed up and slow down. It can twist around the edges of black holes. We can’t touch time, even though our lives are ruled by it. What we keep track of instead are the changes we possess the ability to perceive. A sunset. A grey hair. A seed splitting into a sprout.

Ten years ago, my life was quite different. I was living with my wife in her home country of Iceland in a tiny, quietly terrible apartment, fostering a vitamin D deficiency that would one day make a doctor say ‘no wonder you feel terrible,’ constantly plugging holes in the sinking ship that was our bank account with paycheck after flimsy paycheck. Good sense dictated I should go get a job at a coffeeshop or whatever and stop trying to make the writing thing happen, but I am nothing if not stubborn and a little bit stupid. Instead, I hammered away on a nine-inch netbook I could’ve fried an egg on as it perched upon my knees. I was in the midst of my last rewrites for a book, the first I’d ever written. I’d promised the Kickstarter backers who’d kept a tiny, quietly terrible roof over my head the previous spring that I could do this, that I could finish this manuscript and get it out into the world. The trouble was, I didn’t know if I actually could. I’d never done this before. And I was scared all the time, scared that I would fail, scared that my ideas sucked, scared that I would let people down.

Today, I am sitting in the house that my wife and I own in my home state of California. I took my vitamin D capsule with breakfast, as I do every morning, and I no longer agonize between bills and groceries. I’m writing on a thirteen-inch, super-fast laptop resting in glacial calm upon the ergonomic lapdesk that I believe claimed to be made of ‘eco.friendly materials,’ which I suspect is bullshit in one form or another. If I glance up over the screen, there’s a ladder shelf leaning against the opposite wall. It’s got many books on it, all of them by me. It’s got notebooks filled cover-to-cover, each of which is tabbed and dog-eared and has travelled the world. Alongside these are curios gifted to me by people on those trips – folks at bookstores, at conventions, over café tables where I couldn’t read the menu and was delighted to try what.ever got put in front of me. There is framed fan art hanging on another wall, a pair of Hugos sitting on the mantel downstairs, a Scrivener file on this hard drive that will become another book in turn. And I am scared all the time, scared that I will fail, scared that my ideas suck, scared that I will let people down.

A year is a measure of a closed orbit. A closed orbit means you return to the point you started from.

One question I get asked often and have yet to come up with a good stock answer for is that of where my titles come from. The honest-to-God truth is ‘I just throw words together until it feels right,’ but this never satisfies the asker, so I always have to fumble around until I man.age to sound smarter than that. Okay, so, if I dig a bit deeper: a title can’t feel right until I know the core concept I’m aiming for. Much to the chagrin of my very patient publishers, I don’t title my work until it’s done, or close to it. I don’t outline, either, and I don’t write linearly, so I have no idea what it is I’m writing until I’ve written it. I was at a loss, at first, over what to call this meandering collection of road-trip stories in space, which had no real protagonist and only a hint of plot (both qualities by design), expressly intended to challenge the idea that science fiction had to be about explosions, high drama, and lone heroes on pedestals. I had grown up feasting on space opera, and sometimes there reaches a point where you love a thing so much you want to crush it in both hands and mould it into something else.

But what was this book about?

This was the thing that hamstrung me for years before I finally sat down in 2012 to cobble those notebooks full of half-baked ideas together. I believed, wholeheartedly, that I didn’t have a real science fiction novel in front of me, that this wasn’t a real book. All I had was vibes and conversations, I thought. Nobody would like this, and how could they? I couldn’t even explain what this was.

It was a book about people, the stubborn part of me replied. It wasn’t about the entirety of their lives – those had begun elsewhere, and would keep branching after the fact. It was a book about a single stretch of time in nine respective lives, a temporal cake slice they all shared. But you can’t measure time. You can only measure the perceivable movement within it.

The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet.

It’s funny that I thought of this book as a time capsule in a narrative sense, because both it and every book I’ve written since serve as time capsules of me as well. I think all books do. If anybody ever asked me to write an autobiography, I’d just tell them I’ve already written and am writing it, and will be doing so forever. When I look back through The Long Way, after I stop nitpicking the ten thousand things I would change, I see nothing but my twenties. When Rosemary wakes up in the deepod miserable and groggy and needing to pee, I see myself, bleary-eyed on transatlantic flights during the early years when my wife and I stuck it out long distance. When Jenks and Lovey talk all night without being able to touch, I think of the endless months between those visits (and the phone bills we racked up). When the gang meets the modder sibs on Cricket, I see the house I shared with friends the year before I moved to Iceland. I see a coworker I couldn’t stand in Corbin, my late-night existential tangles in Ohan, the kinds of people I wanted to be in Ashby and Sissix. Every member of this crew is me, tip to toe. They’re also nothing like me, not even a little. It’s just a story, after all.

The me I am now couldn’t write this book as it is, even if I wanted to. I look at the girl in my author photo from that time – taken by a friend, on her couch, when her now-tween son was a baby and her daughter didn’t exist yet – and I couldn’t be her again. I know her, but I don’t know how. And as such, I can’t be the crew of the Wayfarer anymore, either. I’ll always know them, too, inside and out. I can tell you without putting any effort into it that if Dr Chef overheard me saying I’m afraid of letting people down, he would make me a cup of boring tea and tell me to come chat with him while we harvest vegetables together. I can tell you that Kizzy would explain orbits and the ephemerality of time with a few ball bearings she yanked out of some machine that shouldn’t have things yanked out of it. I can tell you that, yes, Rosemary and Sissix are doing great. But their voices are something I can’t summon anymore, not in a genuine way. I’m not melancholy as I write that – far from it. It’s merely a measure of movement, like the stamps in my passport or the wrinkles I’m getting around my eyes (I love them, for the record). I’ve changed; the Wayfarer never will.

But there are things that me today and me ten years ago have in common, just as I can say the same about the mes that existed fifteen, twenty, thirty years ago. My mom sometimes jokes that I didn’t get older, I just got taller, and when it comes to things like space and bugs and books and video games and trips to the museum, she’s right. In regards to this work, though – the one you’re holding now – I may not be the person who wrote this anymore, but what she and I will always, always agree on is this: when you exit the airlock into that patchwork metal corridor, when you are greeted by an AI and a feathered alien in short succession, when you adjust to the artigrav and have a look around, I want you to feel safe. I want you to know that you are wel.come in this corner of the galaxy exactly as you are, and you can live a good, satisfying life here, if you want to. There is always a place for you at the table, a chair that will fit your body, a meal that will suit your needs. If you fall, someone will come running. If you are hurt, you will heal. You can wonder. You can rest. You can ask questions and grow. You can fuck up irrevocably and still be loved. You are loved. How could you not be? You are a piece of the universe, blood and thought and bone. And what is the universe, if not beautiful?

Come out of the open and into our home.

–Becky Chambers